Recording Circle of Magic Audiobooks with Bruce Coville’s Full Cast Audio

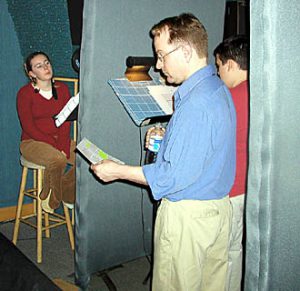

(See Photo Galleries for numerous production stills.)

In 2001 or 2002, I forget which, my friend and fellow writer Bruce Coville approached me about recording my Circle of Magic quartet with his new audio book company, Full Cast Audio. Because of my background in doing radio during the 1980s, I was thrilled to have the chance to get in front of a microphone again and to hear my characters given life by a group of good actors. There is no feeling quite like it. With movies and television, the studio’s choice of actors and visual details never quite matches the way anyone, particularly the author, imagined the story. With audio productions, though, the right actor can give the listener’s imagination an extra hook on which to hang her/his imagination, the extra boost that makes the book live in the listener’s mind.

Of course, that was what I’d learned of voice productions during the 1980s, when I chose the actors who performed my audio plays, to the point of writing parts with particular actors in mind. I knew that Bruce had done full cast books for years with Listening Library, before it was bought by Random House, and now with the Full Cast Audio company. I knew he had a great ear for voices. But I didn’t know if he would have people who would match what I’d had in mind as I wrote, and I wouldn’t be directing them; Bruce would. (He and his company had to work with a risk in my case, the possibility that, because I’d done audio productions before, I might try to impose my views on their actors and working style.) (Bruce would find out later that, rather than think I would tell them how to do it right, I was yelping, “No responsibility! Whee!”)

I was also nervous on my own behalf—I would be the narrator, and I hadn’t been a voice actor in over a decade—and that of my husband Tim. Bruce had said he’d cast Tim in something, since Tim knows my characters and stories as well as I do, if not better (I forget a lot of details in the Chase for the Next Book), but we weren’t sure how much he’d be able to use Tim. That was a worry. You see, my beloved Spouse Creature was an actor before and at the same time he was a radio actor. Like most actors, he believes the wise old saying about “there are no small parts, only small actors” is a keg of crocodile puckey. It’s different when you’re in a company like our radio company or like Full Cast. There’s always the chance for a big part in the next production. We, however, were just there that first year to do one book. If Tim got a tiny part, he was going to sulk.

Our journey began in Framingham, Massachusetts, the Sunday after the close of the Boskone science fiction convention. We followed Bruce and his family back to Syracuse, priding ourselves on getting lost only twice. (We happen to have a record for getting lost at least once on any trip, and we work hard to maintain it.) Driving behind “Lead Foot Coville,” as Tim promptly named him, was an exercise in the art of keeping up. Since Bruce is that way most of the time, I don’t know why I didn’t expect it from him as a driver, too. When Bruce is on the move, he leaves little more than a blur behind.

Full Cast put us up in a suite hotel, which is more like an apartment building than a hotel: the residents get a kitchen, bathroom, living room and bedroom. All I cared about that first night was going to bed. All Tim cared about was finding a grocery store so he could buy things for the refrigerator. At that time, we lived in a one-room studio apartment with a kitchenette—I didn’t realize that having a full kitchen with a large refrigerator would drive Tim a little crazy.

The first two nights were rehearsal nights at the Full Cast office. Everyone took care to point out to me that this was the first time they’d been forced to put two long worktables together and use extra chairs because the cast was so large—fifty speaking parts, with a total of twenty-three actors, several playing more than one character. I kept muttering that with the Circle of Magic books I was trying out a large tapestry, a crossroads of the world and a cosmopolitan mix of cultures, until by the end of the recording sessions I just mumbled “large tapestry, crossroads, cosmopolitan mix” and everyone knew what I meant. Bruce introduced me to Full Cast’s business manager, Dan Bostick, who is a wee, elfin, red-headed fellow with a maniacal aptitude for puns, as if I weren’t already up to here in puns with Bruce.

Bruce and Dan had already cast most of the major parts from FCA’s “stock company” of over seventy-five voices. Those voices belong to actors from the area and (sometimes) their relatives. Syracuse University and community theater provide a number of members of the stock company, which includes acting teachers, veterans of school and university plays and musical theater, dancers, and singers. The man who played Duke Vedris, Gerard Moses, is a retired professor of drama and a director of theater and opera who looks like a very happy elf when he grins. He has a deep voice that gives Vedris a lot of presence, but he can also sound like a total slime, as he did as the evil mage Enahar in Tris’s Book. I had to keep looking out of my narrator’s corner to make sure that disgusting person was really Gerard! Lark, another adult character, was read by Cynthia Bishop, a librarian and professional storyteller, who—completely by coincidence—has driven a car with the license plate “Lark” for the past ten years. Prickly Rosethorn is voiced by Mo Harrington, a singer/actor/stage director, and Frostpine, Brian Pringle, is a drama teacher. We had two Sandrys, two Briars, and two Trises during the three years we took to tape the quartet (these teenagers! always running off to start their own careers or go to college!), while Gabrielle Barry-Caulfield (Gabe) spoke for Daja in all four books. The actor who played Niko was my suggestion, because from the moment I’d first heard Bruce Coville speak (except for that time he was doing goblin voices), he sounded exactly as I’d meant Niko to sound. My beloved Spouse-Creature Tim not only ended up as a utility infielder, reading a guard here and a merchant there, but he also landed two very nice parts: that of Dedicate Crane in Sandry’s Book, Tris’s Book, and Briar’s Book, and the frustrated mage Yarrun Firetamer in Daja’s Book. (My hat’s off to Tim. Those were two of the hardest characters to like in the quartet, and he made them human.)

Carrie Manalakos, who was in her senior year in high school and was preparing to start at New York University in the fall, was Sandry for the recordings of Sandry’s Book, Tris’s Book, and Daja’s Book; Katie Reed stepped in for Briar’s Book. Darrin Revitz, about to graduate from the Syracuse University theater program was Tris for the first three books and Carmen Viviano-Crafts, a Full Cast veteran with a number of wonderful performances for the company, was Tris’s voice for Briar’s Book. Gabrielle Barry-Caulfield (Gabe) has been in high school and performing at Renaissance fairs during the years she has played Daja. Spencer Murphy, who started out as a middle-schooler with a sheet of acting credits as long as my arm, was Briar for the first three books; Karam Anthony stepped in for Briar’s Book, because—ahem—Spencer went and got older on us (he doesn’t sound like a ten-year-old anymore, folks).

Carrie Manalakos, who was in her senior year in high school and was preparing to start at New York University in the fall, was Sandry for the recordings of Sandry’s Book, Tris’s Book, and Daja’s Book; Katie Reed stepped in for Briar’s Book. Darrin Revitz, about to graduate from the Syracuse University theater program was Tris for the first three books and Carmen Viviano-Crafts, a Full Cast veteran with a number of wonderful performances for the company, was Tris’s voice for Briar’s Book. Gabrielle Barry-Caulfield (Gabe) has been in high school and performing at Renaissance fairs during the years she has played Daja. Spencer Murphy, who started out as a middle-schooler with a sheet of acting credits as long as my arm, was Briar for the first three books; Karam Anthony stepped in for Briar’s Book, because—ahem—Spencer went and got older on us (he doesn’t sound like a ten-year-old anymore, folks).

Right here was one major difference between my radio company and Full Cast: Full Cast puts real kids in kids’ parts, rather than use an adult as many people working in audio prefer to do. (I have since suggested that Full Cast have a sticker on the box: “Made with 100% real kids!”) I wasn’t convinced that all of Full Cast’s choices would work right away, but Carrie and Spencer were Sandry and Briar from the very beginning to me; later, as I listened to them, Darrin and Gabe proved they were Tris and Daja. They read, fumbling with my made-up languages and strange names, but all four kids and their teachers had a presence that made me feel that my characters were starting to poke their heads out of my brain to see what was going on. When Katie, Karam, and Carmen stepped in, they were every bit as real and vivid. My kids had gone from the page to the real world, planning, fussing, learning, groaning, being scared and acting brave. Forget movie rights. This is perfect theater, with the people drawn in the listener’s imagination, and the voices to convey new emotions, relationships and ideas. No film company could do as well with a book. No, not even Peter Jackson or Hayao Miyazaki.

For two nights that February, then in January 2003, and January 2004, we packed around two long tables, getting fed and watered regularly. Here I could listen to the first tendrils of the performances as we rehearsed, reading through the books as Bruce cast smaller voice parts from a pool of actors. Actors quizzed me on pronunciations, always tricky with a separate world fantasy, and on character backgrounds—or at least they did if they could find me that first year. That time I hid a lot: I’m shy (no one believes me, but it’s true, especially when I’m not being my public author self). I didn’t know what to say to these people who made my dreams three-dimensional. It hadn’t never occurred to me that they might want to know the backstory on my characters. Luckily, Tim knows my people as well, if not better than I do, because we often talk about the characters I’ve created in both universes, who they are, and where they come from. Until I realized the actors really were deeply interested, Tim filled them in.

During rehearsals we also check those parts of the script where Bruce and Dan could determine when the words “s/he said” could be eliminated, because listeners would recognize the actor’s voice in a short exchange. (One thing people who are unfamiliar with audio don’t realize: if the audience doesn’t hear a character fairly often, they forget that s/he is present, or who s/he is. Sometimes “Jane Doe said” is redundant; sometimes it’s needed to remind the listener who is speaking.) This is a big deal. FCA is very firm on things being done as the writer wrote them. The writer must approve cuts and pronunciations. If a “g” is not dropped from a character’s line in the text, Bruce and Dan will not allow it to be dropped during recording. Not even when I thought it was okay! Gee, these guys are strict! After hearing of the treatment writers get at the hands of movie studios, though, I thought it was very nice to be consulted on even small details.

After rehearsal, we went into production at the Todd Hobin studio outside Syracuse. Scheduling was as precise as the “anything that can happen, will happen” law of showbiz will allow. People are given a schedule: they don’t have to arrive at the start of taping to wait all night until it’s time to work, and they don’t come and go in a steady, distracting stream. The schedule shows what material (chapters and pages) will be covered each night and at approximately what time it will be covered. Times are set for director and actors to tape “wild lines,” one or two line bits when the performer might have to otherwise wait for hours to record them. Recording times are guesstimated from the complexity of the material, with more time and fewer pages set for those nights when a lot of characters are on mike. Parents know when to pick up their kids, so they aren’t kept waiting.

Of course, we always had to work around the Syracuse weather. During our first year, the temperature never went below forty degrees, and while it rained nearly every day, it snowed only once. Everyone kept telling us, “This is not normal.” The next year, we came to the Tris’s Book rehearsal in a blizzard. It snowed a little every day for two weeks and a lot on some days. For someone who had never driven in snow before, Tim did a great job, and just as well—he got lots of practice that year and the next. On the Wednesday night recording session for Briar’s Book, a mega-blizzard blew up out of nowhere. By the time Bruce decided to cancel the session, Tim had already begun to drive to the studio. To the astonishment of all (when a Syracuse-based company calls a close-down for snow, it is for can’t-see-to-drive snow) he not only reached the studio, which is off the main roads, but managed to return to me safely at the hotel. I was so relieved to see my California boy!

While actors recorded, the rest of the cast settled into the green room to wait. There was even a special soundproof booth where the kids, who were carrying full school loads, could do homework, play games, or just snooze. People brought books to read, needlework to do, and music to listen to. Tim, the technoweenie, started bringing old laptops and computer games for people to play, since we always have a bunch of them at home. That’s the less glamorous side of any acting job: waiting to go on. They also could hear the recording session as it was going on, an important necessity when someone has to take a bathroom (or in Tim’s case, cigarette) break, or when Bruce needed to summon the next group to speak on mike. I know most of these things from hearing about them: as narrator, I was always on one of the five microphones. It sounds like fun. Maybe I’ll write a book with a kid as narrator, as in James Howe’s The Misfits, Doug Cooney’s The Beloved Dearly, and Robert A. Heinlein’s Have Space Suit—Will Travel. That way, I’ll get to relax and wait till they get to my part. (When books are told by the main character, the author often is cast as an actor. Paula Danziger was a French teacher in United Tates of America, and Bruce was Gaspard the lizard man in The Monsters of Morley Manor.)

While actors recorded, the rest of the cast settled into the green room to wait. There was even a special soundproof booth where the kids, who were carrying full school loads, could do homework, play games, or just snooze. People brought books to read, needlework to do, and music to listen to. Tim, the technoweenie, started bringing old laptops and computer games for people to play, since we always have a bunch of them at home. That’s the less glamorous side of any acting job: waiting to go on. They also could hear the recording session as it was going on, an important necessity when someone has to take a bathroom (or in Tim’s case, cigarette) break, or when Bruce needed to summon the next group to speak on mike. I know most of these things from hearing about them: as narrator, I was always on one of the five microphones. It sounds like fun. Maybe I’ll write a book with a kid as narrator, as in James Howe’s The Misfits, Doug Cooney’s The Beloved Dearly, and Robert A. Heinlein’s Have Space Suit—Will Travel. That way, I’ll get to relax and wait till they get to my part. (When books are told by the main character, the author often is cast as an actor. Paula Danziger was a French teacher in United Tates of America, and Bruce was Gaspard the lizard man in The Monsters of Morley Manor.)

Everyone was cheerful with the wait, partly because there were always munchies around, and partly because Full Cast believes in feeding people well at the dinner break. That first year, I didn’t know what to do or say around the actors, so I mostly hid in my corner—Bruce actually urged me to come out with the others at one point. Tim had no problems socializing: he could talk computers and games with the kids, engineering technology with the production staff, and cameras, books, movies, plays, and musicals with everyone else.

While we recorded during those three years I got to know our engineers. Todd Hobin is a handsome, bearded, gentle-voiced man who made his career performing hard rock `n’ roll. Tim and I couldn’t believe this at first. Todd hardly ever raises his voice, and he usually wears a bulky cardigan around the studio, like somebody’s dad. This year he gave us some Hobin Band CDs. As we listened to the first one, we kept staring at each other as this growling, wailing, guitar-whomping guy poured out of our speakers, and we kept asking, “Todd?” Todd is a very reassuring man for a skittish, shy author to work with. He has also been the composer for most of Full Cast’s music, writing tune that go from lazy jazz (in Elizabeth Winthrop’s The Red Hot Rattoons and James Howe’s The Misfits) to the Islamic/Hindi flavored pieces (the Circle books) to Chinese-influenced material (Geraldine McCaughrean’s The Kite Rider). Todd is one of the most versatile composers I’ve ever encountered.

In addition to Todd as our engineer, we worked mostly with Ata Pinto, who is very tall and precise, and Brent Hobin, Todd’s son. Both they and Todd are far more patient with us than other engineers I have known. Patient engineers are really important when members of the company flub a line so many times it becomes funny and everyone collapses with the giggles. Then there are those moments when the engineers have to stop the recording for mouth noise, paper rustle, lip smacking (yes, they can hear dry lips move on those headphones), and the ever-popular “outside noise.” I got a taste of it recording Briar’s Book, when they put me on headphones, too, so I could hear even the smallest sound. That was the time when Tim cleared his throat on the microphone one time too many. Bruce saved Tim’s life by restraining me, asking everyone else to take off their headphones, putting the headphones on Tim, and telling Tim to clear his throat on microphone. Tim never did it again. (He’s a quick study.) In our three years of recording my books, the engineers and cast had plenty of other annoying sounds to cope with. We had to stop for trucks, airplanes, cars (there just are no mechanical vehicles in Emelan), and the noises people make when coming to and going from the studio. I have been told that in summer it’s worse: all that plus lawn mowers, motorcycles, and boats. (The studio is behind a good-sized stream.) Bruce tells me I missed the outside noise of all outside noises: the day the fellow across the road decided to move his house. As in, lift the house with machinery and move it to the other side of the property. Nobody ever moves a whole building in New York City.

Except for Briar’s Book, when I was recovering from the flu, I tried to do as much of my recording while standing because, like Bruce and most singers and voice actors, I know I have more energy when I work standing. That meant I was on my feet for at least half of every recording session for the first three books. I knew I was dealing with people who respected the author, because no one ever asked why, during every break, I could be found bent over a stool (stretching out my leg tendons and keeping my weight off my feet). Bruce too stood throughout the entire experience, and never once bent over a stool or sat and cuddled his feet. He remained crisp and vigorous during halts to bring on new actors and take off old ones, reset microphones to the voice levels of new performers, and wait out noises, giggle fits, and meals. Dan’s energy was also a brisk and crackly affair. They’re very tiring for a sloth like me to be around.

Except for Briar’s Book, when I was recovering from the flu, I tried to do as much of my recording while standing because, like Bruce and most singers and voice actors, I know I have more energy when I work standing. That meant I was on my feet for at least half of every recording session for the first three books. I knew I was dealing with people who respected the author, because no one ever asked why, during every break, I could be found bent over a stool (stretching out my leg tendons and keeping my weight off my feet). Bruce too stood throughout the entire experience, and never once bent over a stool or sat and cuddled his feet. He remained crisp and vigorous during halts to bring on new actors and take off old ones, reset microphones to the voice levels of new performers, and wait out noises, giggle fits, and meals. Dan’s energy was also a brisk and crackly affair. They’re very tiring for a sloth like me to be around.

Usually the director has his own microphone. For the Circle books, that was Bruce himself. For the first three books, he stood in front of the three microphones where the actors worked, with soundproof walls to keep the actors’ voices from coming in on the narrator’s microphone. That first year, the only person who could see me was Bruce, which was a good thing when it came to the big marketplace fight in Chapter 8, the one where we had twenty-three people sharing the microphones. (How do you manage that? You do the Microphone Dance, when one person speaks directly to the mike—it’s so sensitive that if you move so much as an inch you will sound different—then steps away to let the next person in.) They took pictures of the twenty-three people sharing three microphones, while I hid behind my little wall and mumbled about crossroads and cosmopolitan mixes of culture.

Sadly, during those first two years, it was being tucked into a little narrator nook that brought me to grief. I have to confess something here. Everyone who knows me well knows I have a dreadful problem with, well, bad language. I am a potty mouth. The more comfortable I am, the worse my language gets, particularly when I wish to deliver an opinion. During the first year, that wasn’t a problem. Because the source of most of my aggravation was Mr. Wise Guy, Mr. Cranky, Mr. Director-Who-Always-Has-an-Opinion, Mr. Let’s-Pick-on-the-Author-Who-Didn’t-Know-We’d-Be-Recording-Her-Book, Mr. Coville, who was also the only person in the room with a clear view of me, I introduced him to my large and expressive vocabulary of obscene gestures. I have collected them from all over the world, and he got to see all but one (that one is just for my husband). The second year we recorded, he thought he had left me without the ability to express myself: they had reconfigured the studio so that I was completely enclosed. He couldn’t see me. (And after I had learned a few more gestures over the course of the year, too.) That was when he found out that, by using gestures, I was being polite. When I’m comfortable around people, I don’t particularly care what I say to them. Bruce’s anthem for Tris’s Book and Daja’s Book was the cry of “Not in front of the K-I-D-Z!”, as his face grew more crimson with each repetition. (All right, that one time, I didn’t realize that the microphones were still on and that they could hear me in the green room. I said I was sorry!) By the time we recorded Briar’s Book, the studio was re-shaped again so that the actors and the director could see me quite well, and I restrained myself, particularly since Karam is just ten, and a boy really ought to learn some of those words from other boys. Most of the regular cast is over fifteen, except for Spencer (at that time), whose dad was a jazz musician—if Spencer hadn’t heard it, it hadn’t been invented—and the younger kids who came in to record smaller parts. I was good when they were in the studio. Well… as good as I can be when comfortable.

I know that people wondered if I was entirely happy during recording. They couldn’t know (nor did I think to explain until now) that my happy recording face is a scowl, not of anger, but of total concentration on what comes into my ears. Inside, I was on Cloud 9 during those nights when we read and recorded. To hear good actors take my own written characters and bring them to realistic life is wonderful. They laughed at my jokes—the ones I made on purpose! They inspired me with ideas for new stories about these characters, and they made me feel right at home. That is why, on the most grueling night of taping (22 people on microphones, photo evidence), I turned to Bruce and said, “My neck hurts, my back hurts, my feet hurt, and I’m exhausted, so why am I having such a good time?”

Sometimes being a writer is a lot like talking to yourself. You try and tell yourself that you are writing, not talking to yourself, that you are generating stories for others to enjoy, and you handle your published work to remind yourself that success and publication are real. People come to tell you they love to read your books, and most of the time you believe them, or you want to—but you didn’t see them read the books, did you? Well, for three years I have watched and listened as a large group of talented people of all ages read my books aloud, bringing their own imaginations and skills to my characters, directed and recorded by talented people who had their own polish to add. I saw people’s faces light up as they read or listened to what I had written, and saw their deep concentration as they plunged into dramatic scenes that touched on their own experiences. I heard their jokes and saw them insist on getting every word just as it should be. I had created something of value, something that other busy, talented people thought was worth time and labor and expense to perform. Full Cast Audio erased my last questions about what I had achieved. I wasn’t talking to myself when I wrote these books. I was telling real stories about real lives, lived by people whose voices now sound in my head as I write my next Circle book. That’s a gift I can never buy elsewhere, and certainly never forget.

Circle of Magic, Circle Universe, Full Cast Audio, Personal Sketches, Photos, Spouse Creature, Tammy Speaks