My Mundane Jobs

Behold the latest of my ever-changing addition to a basic biography that doesn’t change much. Call them snippets from my own mental scrapbook:

Babysitter (duh), 1966 – 1972: The first time I babysat an infant boy, I begged my mother to change his diaper. Instead she laughed herself silly and told me to do it. (To her credit, she did talk me through the changing process, which I’d never done before, but she still laughed till she turned purple over me changing a little boy. I’d never seen one before!)

Census Information Taker, 1970: For one week. This is the kind of job that introverts dream they have to do in Hell. My mother had the job, so she handed some off to 16-year-old me.

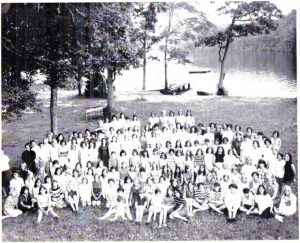

Tobacco Farm Worker, 1970: The way this worked, the company gathered up a bunch of teenagers in Pennsylvania (and Indiana, and Florida), and shipped us all to various farms for the summer. Mine was in Massachusetts, where we girls shared the labor with Puerto Ricans. Part of it was summer camp, which I’d never done. But the work part was hell for me: early in the morning to the fields, into the rows, bend, wind the cord around the stem of the plant clockwise without breaking the leaves, then reach high overhead and tie a particular knot to the wire that ran up there. Cut the cord, on to the next plant. We were in giant tents, so it was stiflingly hot all of the time; heatstroke was an issue for a pale kid like me. But if we didn’t work, we didn’t get paid, and we had to finish a set amount of rows before we even got minimum pay. When we were finished, our arms were covered with brown nicotine sap to our elbows. There was always a rush for the showers when we got back—the showers or the TV, because Dark Shadows was on right when we came in. I thought I was the only person in the world who loved Dark Shadows, a soap opera with a vampire hero!

Tobacco Farm Worker, 1970: The way this worked, the company gathered up a bunch of teenagers in Pennsylvania (and Indiana, and Florida), and shipped us all to various farms for the summer. Mine was in Massachusetts, where we girls shared the labor with Puerto Ricans. Part of it was summer camp, which I’d never done. But the work part was hell for me: early in the morning to the fields, into the rows, bend, wind the cord around the stem of the plant clockwise without breaking the leaves, then reach high overhead and tie a particular knot to the wire that ran up there. Cut the cord, on to the next plant. We were in giant tents, so it was stiflingly hot all of the time; heatstroke was an issue for a pale kid like me. But if we didn’t work, we didn’t get paid, and we had to finish a set amount of rows before we even got minimum pay. When we were finished, our arms were covered with brown nicotine sap to our elbows. There was always a rush for the showers when we got back—the showers or the TV, because Dark Shadows was on right when we came in. I thought I was the only person in the world who loved Dark Shadows, a soap opera with a vampire hero!

On weekends we went shopping, cleaned up our area, went to movies or had a dance, went to the church of our choosing (Baptist or Catholic—I’d had a bad experience with a hellfire Baptist preacher when I was 6, so I went Catholic), then had an outing. It was on one of these, swimming in a lake, that a girl with actual purple eyes popped out of the water right in front of me. I never forgot her, as my readers know.

Then we were out of the fields and into the sheds. There you were either a sew-er, feeding the bottom of the stems of two huge leaves at a time up into the clashing metal needle that shot through them, threading them onto the long cord that attached them to a long slat of wood called a “lathe.” I tried sewing, but I was too slow and too afraid of getting my hands caught in the needle. Fast sewers could make extra money, but I would never be one of them. I was put to carrying four lathes with heavy wet leaves over to the men who hung them in the rafters high overhead, where they would dry. The stink made me sick. The work made me sick. And I could sense a growing hostility from the girls, who thought I believed I was too good for them. I had heard the stories, of previous summers when factions in the houses heated up into major brawls, with groups fighting against one another and finding individual girls to beat up. Having been singled out before as a weirdo and realizing I wasn’t going to make the kind of money that would help me toward college, I called my mother. That weekend I found myself on a bus, headed home after six lousy weeks. No matter what kind of job I had later, no matter how much I disliked it, I could tell myself, “It’s not the tobacco farm.”

Maid in a residential hotel, 1972: My mother again, sharing the work of making beds, cleaning bathrooms, vacuuming rugs. It only lasted a week, thank heavens.

Letter Reader/Writer for a man who could not read, 1971 – 1972: The same residential hotel—we lived there. Paul lived down the corridor. He offered to pay me to read family letters to him and to write letters from Paul to his family. I was a senior in high school and could always use money for things like nylons. I would have done it for nothing—he was a very nice man, a retired train worker, but he insisted on paying me. When I left for college, he gave me a watch and thanked me. I asked my sister to take over. I don’t know who wrote his letters after my family moved.

Waitress, Griffith’s Restaurant, 1972: My first real job, at ninety cents an hour, but I’d make it up in tips! I was told. It was an experience. If I’d thought I was an odd bird in all my school experiences before, I was really the odd girl out here. I worked with two older, blue collar women, and as long as I behaved and showed proper respect I was okay. My problem was that I don’t always think before I speak, and what I think is funny sometimes gives a lot of offense.

Waitress, Griffith’s Restaurant, 1972: My first real job, at ninety cents an hour, but I’d make it up in tips! I was told. It was an experience. If I’d thought I was an odd bird in all my school experiences before, I was really the odd girl out here. I worked with two older, blue collar women, and as long as I behaved and showed proper respect I was okay. My problem was that I don’t always think before I speak, and what I think is funny sometimes gives a lot of offense.

Also, people seemed to think that because I was going to college, I thought I was better than they were. I was confused—I knew where I had come from, the single hotel room for my family, the four room house with an outhouse, and the very blue collar relatives who took us in and got us on our feet when we came back from California. I may have made jokes that weren’t as funny as I thought they were, but I never thought I was better than them, because I wasn’t, and I knew it. I was just going to college.

They thought that because I was going to major in psychology, I was going to analyze them. I had seen what happened to a friend when her psych major sister, home on vacation, “analyzed” her love of chocolate cake. I promised myself I would never to that to anybody. It was also the kind of thing my mother did all the time: putting Freudian motives to my love of fantasy, making me feel dirty. I was never going to pry into someone else’s psyche and make them feel bad.

There was one good thing (besides money for new clothes and luggage). I’d spent my school years being ignored by boys, or scorned by them, which was worse. In my senior year, I finally attracted the attention of, and dated for a time, a college junior. (He became Duke Roger.) And while I was waitressing, it wasn’t so much that I discovered boys, but that they discovered me. Or rather, young men discovered me. It was the seventies; I’d been raised to believe I could do what I wanted with my body—let the good times roll! I flirted, and they flirted back. I even dated! It was amazing, after the sneers and laughter I got from girls and boys in high school and middle school over how attractive I was (not).

The work was so-so. I didn’t like the people who treated me like a personal servant, and I really came to appreciate the hard work waitresses do. I learned that often the best tippers are those who have worked in food service before, because they know the pay is low and tips are the only real money people make. I never tried to wait tables again, but it was a very educational, and in some ways liberating, experience.

Tutor, West Philadelphia Free School, 1972 – 1973: My Work-Study job for my freshman year. The West Philadelphia Free School was for kids who were struggling in the huge West Philly high school, whose teachers thought they’d do better with smaller group classes and tutors. I worked with kids in English and social studies, homework help mostly.

Babysitting, Society Hill, 1973: When my grant money for Work-Study ran out in the spring semester, I got a job babysitting for a Wharton professor and his wife, so she could mainly have quiet to finish her doctoral dissertation. Brian, who was four, and I got along pretty well. We went on walks in Society Hill, which is one of the oldest parts of Philadelphia. Then it was back in time for Sesame Street. This was my first exposure to the show, despite Big Bird’s “Rubber Ducky” topping the pop charts the year before. I fell in love with Oscar the Grouch and Animal. Unfortunately, the show had a time limit, and Mr. Rogers was next. Brian and I always argued about Mr. Rogers—he loved him, and I hated him. I hated his voice, and his preciousness, and I even hated the way with which he folded his sweater. But it was Brian’s house and Brian’s rules, so he always won the argument, and laughed at me because he won. Afterward, we played with his toys. I really liked that kid. It never occurred to me that I interacted with him at a higher level than ordinary four-year olds. He was just Brian, the kid of two very intelligent parents. Now I know he was probably very gifted. I wonder what he’s doing now?

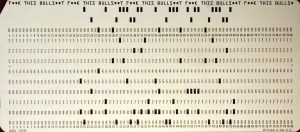

Psychiatric Research Assistant, 1973: My job during that first long, hot summer at Penn was as a research assistant for a joint study being conducted by a psychiatrist and a doctor in psychology on the effect of weather and atmosphere on psychiatric contacts at Philadelphia General Hospital, the catching hospital for West Philadelphia, over the course of several years. Along with two other girls, I plowed through psychiatric records of admissions and symptoms, filled out the diagram our bosses had generated, and then—to my horror—went to the Penn Computer Center to enter our data on punch cards and run them through the feeder.

I’d better explain, this was 1973. Computers were huge things kept in cold rooms, and we interacted with them by feeding data punched cards through a hopper. Woe to the person who fed a bent card! The hopper jammed, cards flew everywhere, we had to gather them up, try to put them in order (they weren’t numbered in order), repunch a new copy of the bent one (think of having to hit each key on your keyboard really hard, and if you make a mistake, you have to get a new card and start all over—no erasing), put that in the right order, and start again. And then there’s the wait for the hopper. I once had a session go wrong four times in one day. My fellow workers gave me the Computer Center of the Year Award—two punched cards with obscenities expressing my feelings about computers.

Then we took the computer’s correlations back to the office and entered them on the diagram to see what meshed. I continued with the job once the school year started, gathering data on weather conditions from microfilm at the Philadelphia Public Library until my grant ran out.

Childcare, Penn professor, 1974: I thought that I would be better at this than I was, but several rambunctious kids and a grocery budget I couldn’t make work were my downfall. Luckily my boyfriend helped with the cooking (he was a far better cook than I was), and the professor’s wife returned to him.

Historical research, 1974: I pulled books from the library or confirmed the library had them for a history professor for her research. Not thrilling, but it paid.

Registrar’s Office, University of Pennsylvania, 1974: Serious grunt work: assembling paper documents, stapling same, folding and stuffing them into envelopes, sticking address labels onto envelopes, stacking envelopes in mailing crates, on to the next mailing. Here’s the senior, junior, and sophomore classes, welcome to the freshman class. I also got tagged to answer phones when the senior office women went to lunch, and because there was an affinity between us (before me, he only spoke to one other woman in the office), I was detailed to work on a research project for one of the assistant registrars, a Vietnam veteran. We got along fine and I loved working for him. (I had a tremendous crush, but he was very much in love with his wife.) The job in general, with the mail assembling and stuffing crew, was scut work, but the crew was fun. We listened to music and hung out at lunch and after work. Good summer time.

Part-time Student Social Worker, 1974 – 1975: Since I was taking some graduate social work and education courses by then, this looked like a no-brainer. I invested in a couple of blouses and skirts (I was a full-time jeans and t-shirts/flannel shirts hippie by then) and went to work for the Philadelphia Public Defender’s Office Juvenile Court Social Work Division. At 14 hours a week, I had a 40-kid caseload. My job was to find resources for my kids—group homes, counseling (if available), public money (if available), track and notify them of court dates/counseling dates/psychiatric interview dates—get them small things if I could, record their side of the story to compare to the version recorded by their defender and by the cops, and show up in court with them. I also visited them at the juvenile detention center if I could.

The majority of my caseload—of everyone’s caseload—was gang youth, and there was little I could do for them because they wouldn’t talk. They had been told the gang would look after them and would punish any leaks, so they were even more tight-mouthed than my relatives, and I didn’t believe there was anything more tight-mouthed than a hillbilly. (I’m an aberration.) Regarding the other kids, there was something I could do for a handful of them, the right thing I could do for two of them, and not nearly enough for all of them. Not enough resources, not enough money, not enough time for any of us who were trying to catch these kids before the system devoured them. I sorta burned out, but thankfully managed to do it right around when the Work-Study money ran out. The funny thing? Work-Study paid for me to be there. The Temple Social Work students who were there four days a week weren’t paid. This was work time that went to their degrees.

International Student Services, University of Pennsylvania, 1975: Mostly clerk-typist stuff, typing up passport forms (two mistakes and you had to get a new form!) and other forms to get students to school and back to their home countries at the end of the year. There was also assorted correspondence, envelopes for fliers, and answering phones. The crew there was wonderful—very multi-culti and multi-lingual (I felt like a real hick for not continuing either my French or German, both of which I dropped after level 3). Anya was from Yugoslavia and brought me up to date on what had happened since her parents had to leave—quickly. Our boss had been around the world a zillion times and had tchotchkes from every stop. The office was hung around with plants; an easy place to work.

Student papers, various, 1976: I’m not proud of it, but I needed the money. I was a guaranteed A in English, history, and film. When the professor handed my last paper back to the girl who commissioned it with a “Now we both know you didn’t write this,” I accepted the handwriting on the wall and stopped doing it.

Measuring houses, Kingston, New York, 1977: Yep, your eyes do not deceive you. To revise the city’s tax rolls, the state court ordered that every building be re-assessed to full market value (taxes are set depending upon market value of a building, and up until then Kingston was taxed based on a percentage of market value). For this purpose, a bunch of people on Welfare (I’m so not proud of this, but I could not find a job until then) were gathered up, taught how to measure basic buildings, additions, bow windows, attics, and dormer windows (bow windows and dormers add to the amount of livable space), how to fill out the assessment sheet, including notes for things like chimneys (more taxes on working fireplaces), brick exteriors and steam heat (more taxes), and outbuildings and their measurements (garages, sheds, barns). Then we were turned loose on the public.

My team was great. Frank was an older guy whose used car business had flopped. (Did I mention upstate NY was in the middle of an ugly recession? Most of the country was.) Billy was a Vietnam veteran who knew karate. Since on my first attempt to interview a home owner (which is how we got data like chimneys, steam heat, inhabitable basements and attics) had not gone well—I had gotten an extremely hostile, large man who yelled at me, refused to answer the questions, and called the mayor’s office and complained that the team was supposed to have a woman and there were three guys (I wore a bandana and my hair was in a long braid)—I wanted Billy on my team. We made a deal. It turned out Billy didn’t like dogs. At all. I promised to cover the dogs, and Billy would cover the hostile homeowners. It worked out very well, except for the time that one golden retriever not only wanted to show me his very nice doghouse, but also wanted to keep me there. The guys and the owner stood there laughing. Every time I (gently) disentangled my arm from the dog’s grip, he’d re-grip it. The owner finally called him off.

While we did this, we took rainy days to stay in the office and learn to calculate the square footage of each building we’d done. I thought I was going to die before I got the math—and the calculator—down. These days it’s called dyscalculia, and maybe I would have passed college math classes if I’d been taught to deal with it. In those days I was just told I was stupid and I had to muscle through, or flunk. This time, I muscled through, and for all my hard work, I earned the task of teaching other people who were struggling how to do it.

This was also the time that our boss, who was a tax assessor for two small towns in the county and the special deputy for this job, was helping one of his towns stage a tax revolt. He’d talked to us about it, and I suggested a couple of articles markets he might try for publicity. That’s how I became the unpaid publicist for a tax revolt.

This also led to my third sale and my first non-fiction sale, an article for the tax revolt for the magazine The Christian Century. (The earlier two stories, one in 1975 and one in 1976, were romance stories for Intimate Story Magazine. Hey, cash was cash.)

Clerk-typist, Assessor, Towns of Hardenburgh and Denning, New York, 1978: I entered tax record information, answered the telephone and correspondence, let my boss’s Weimaraner have half of my oranges, and worked on publicity for the tax revolt. It was lonely away from my fellow field data collectors, but occasionally they came around to visit.

Housemother, group home for teenaged girls, Buhl, Idaho, 1978 – 1979: At last! A job I was educated for! Obviously it was fate: my dad and stepmother invited me to come live with them in a small town in southern Idaho, which just happened to have a group home for girls which just happened to be looking for a housemother. I was hired to work one week on and one week off, living in, supervising and helping the girls to prepare meals and clean their rooms and the home, administering medications to those who took them, getting the girls to school and home from school, supervising homework and helping them when the tutor was already helping someone else, taking them to doctors and dentists as well as shopping on Fridays, taking them on their Friday night good behavior outing—pizza and games, or a movie, or dancing, taking them on Sunday outings around the countryside (there was a hot springs where we could swim), taking them to after-school events (one of them played junior varsity basketball), meeting with school officials if there was a problem, representing the home at community events, and hosting the monthly Board of Directors meeting (providing refreshments), court appearances and hospital trips (one of each). While I was there, I also helped to cover holiday celebrations, including putting up decorations and preparing meals.

The biggest part of the job, though, and the one that’s hardest to describe, is being a part of the girls’ lives. While I was there I attended one girl’s wedding (her mother signed the papers after she was released from the home), another girl’s false labor (she had the baby on the other housemother’s shift), and testified in court for a girl so she would be placed in a mental hospital rather than our home. Our girls were either judged delinquent or dependent/neglected (their parents were unable to provide an adequate home life and they were chronic runaways). Their babies—another girl had given birth not long before I was employed—were put up for adoption. I listened to their stories, shared my music with them (in the case of my Meat Loaf Bat Out of Hell tape, I gave it to them, since it disappeared after they “borrowed” it), learned disco dance steps from them, and shared the book I was sending out to publishers with them. They liked that so much that I began to write a story with them as heroes, their favorite rock stars as their boyfriends, and all the adventure they desired. Woe betide me if I returned from my week off without at least five pages.

And I listened to their stories. I gave advice when it was asked for, and comfort, and I did not judge. I wasn’t allowed to share my own life with them as a matter of home policy, or I would have told them that my life, and that of my sisters, had not been all that different from theirs. Some of them were defiant through and through, and others hiding deep worries and fears under their defiance. Some were already making plans for their life after the home, while others saw a life no different from the one they had led before they got there. Those of us on staff tried to model a more stable kind of life, one that didn’t involve going to jail. One that involved finishing school and getting a job that paid decently and a home of their own.

I actually used some of my adventures with the girls in a story called “Testing” that was published in my collection Tortall and Other Lands. Some things were changed, but the ways the girls tested X-ray are mostly taken from the ways my girls tested me. The skills they taught me proved very useful in my later life.

They also taught me that teenagers really liked my novel, the 732-page manuscript I called The Song of the Lioness. In a year or so, when a literary agent suggested that I break it up into four books for teenagers, I knew it was a good idea, thanks to my girls. The Lioness quartet is their quartet.

I’m not the only one of us who made good. One of the girls went into the Army; one became a school teacher; one was in graduate school the last that I heard of her; and one did drug counseling. All they needed was people to tell them, “You can do it.” That’s what we did, at the home, and those girls proved they were listening even while they soaped my toilet seat, or slipped extra sausages on my plate when I wasn’t looking, or said “Tell us about the oooolllllllld days, when you were at Woodstock,” or locked me out, or sang Tom Lehrer songs. (If you don’t know who he is, look him up. You’re missing an important part of your education!)

Temporary agency, New York City, New York, 1979: Temporary Secretary, Coward, McCann & Geoghegan; Temporary Secretary, McGraw-Hill Educational Publishing: answering telephones, taking messages, typing letters and lists, filing, typing up edited pages, some editing (which I wasn’t hired to do, but since I could do it, they asked me to anyway). Learning the web of New York publishing.

Literary agency, New York City, New York 1979 – 1982: Office Assistant: answer phones when receptionist at lunch or on vacation; open mail and distribute to assistants or agents; file author book cards (double index card sized, threaded onto metal spindles, set into metal file binders—before computers!), biographical materials, contracts, correspondence, magazine cards; make photo copies; bind and package manuscripts for messenger to deliver to local publishers; bind and package mailings for messenger to take to post office; handle permissions (when someone wants to use a small excerpt from a client’s work and such use is not handled by the publisher, an agreement and fee must be reached and the proper copyright citation must be provided by the agency, i.e., me), send fan mail to authors; play one disastrous game (on my part) on office baseball team; type up telexes (telex is typewriter-like, but it punches holes in a tape and requires much more force to type than any keyboard) and send telex to overseas affiliates.

Agent’s Assistant: go over mail; pull all cards, contracts, correspondence related to each mail item; pull all requested materials; type up correspondence from Dictaphone dictation belt (like a large tape that doesn’t wear out like regular tape from being stopped/started/rolled back); go over contracts at agent’s direction to edit/delete clauses which have been agreed upon with the publisher and client; send gifts to clients/editors/publishers at agent’s request; book business lunches/dinners for agent; handle clients when agent is absent—it doesn’t seem like much compared to the office assistant’s job, but the volume of dictation was much higher, the contract work was very exacting, and the assistant has to stay on top of everything. Additionally, each agent had a different specialty, which meant each assistant had a different specialty, in addition to books. My boss handled sales of book excerpts to magazines, which meant mailing agency books to magazine editors who might be interested; another agency handled the film rights to agency books; another handled children’s books and English publications, and one handled foreign sales. No one complained of anything to do. The head of the company’s assistant, who is now my own agent, chased down copyrights that were about to go out of date and renewed them in his copious free time. He also had the wicked habit of catching me in a quiet moment with an out-of-left-field joke that would make me laugh so hard everyone would come to see what was wrong with me. (And he’d stand there, all innocent baby blue eyes and insist he had no idea. This is why we’re still friends, and I still love going to lunch with these people!)

In the middle of all of this, Claire Smith, who handled children’s writers, took a look at my novel and advised me to turn it into four books for teenagers. This is a tale I’ve told elsewhere, so long story short, by the time I left, I had one book in the stores, and another on the way, with two more in the pipeline.

Temporary Secretary, New York City, New York, 1983 – 1985: I screwed up at the literary agency a few times too many, and my then-boss did me the favor of firing me. (She doesn’t remember it—I reminded her that I was a flake!) Getting fired got me on unemployment for six months, so I could take my book money, buy a new computer, and work on writing. I also realized that working in publishing used up too much of the energy I needed for writing. With that in mind, I returned to the temp business, but in publicity, banking, and finance. There was plenty of down time in which to read and write (by this time I was also head writer for a fledgling radio comedy/drama company), little to no involvement in the lives of my fellow workers, with one exception, a law firm I kept going back to, and I wasn’t burning the stuff I needed to write by working in an industry that was too close to my creative self, like the literary agency. Drawbacks: no health insurance, no paid sick days, no paid vacation, no 401k.

As to my writing life, I knew the likelihood of my being able to make a living at it was unlikely. 8 out of 10 of us don’t make a living at it—I’d learned that at the literary agency. I fit books and radio plays in around my secretarial work, on lunch hours, at night, and on weekends, just like most writers do.

Secretary, Chase Manhattan Investment Leasing, New York, 1985 – 1988: Around June in 1985, my wanderings fetched me up in Investment Leasing at Chase, on the 19th floor at One Chase Plaza, with a view of the Manufacturers Hanover building, both World Trade Center buildings, and the Hudson. All three of the other secretaries in our general pool area were named some combination of Rose: Rose, Rosemary, and Rosanna. At first I was just a utility infielder, but then I was acquired by Valerie, Steve, and Vic, two funny, easygoing vice presidents who soon discovered that if I was allowed to do my own work during downtimes, I was always good for 1:00 AM night crunches. And there were often crunches, because this was the go-go 1980s, where the vice presidents worked the deals, brought in the money, stayed late, and came in early. Steve was in touch with exchanges all over the world, whose players passed him the latest tasteless jokes about world events. Val was the most elegant woman I’d ever met—she soon moved upstairs, to the executive floor. And Vic was a sweetheart from Bayonne who loved his wife and kid and went home in time to hang out while they were still away. Our overboss was an ex-hippie who had come to us by way of London, a man with a freewheeling speech style. Rosanna had to translate his letters and memos into business English, removing phrases like “Man,” and “far out.”

My job was correspondence; mail; such filing as the guys didn’t do on their own; Xeroxing; keeping a record of the Treasury bill numbers; answering phones; booking travel; running things to other floors; sending telexes with the machine that had replaced the finger-hammering typing machine; and the dreaded “books.” Each deal required at least one book, which meant making a number of copies of a document, using an overgrown punch to punch the right number of holes with the right spacing for the binder plastics (woe betide if you got pages in crooked or if you tried to punch too many and got the punch stuck), threading the pages onto the plastic spikes protruding from the rear binder (praying nothing is stuck, crooked, or out of line), threading the top part of the binder onto the spikes, then shoving the thing into the device that cuts the spikes off/melts the stubs into the holes on the top part to give you a solidly bound wad of pages. If all goes well. If some idiot second vice president doesn’t come running up with his section of the book which he only now just finished and it has to go into the middle. So you rrrriiiip the plastic binding strips apart, thinking of the 2VP’s neck as you do, and trudge off to the Xerox machine. Except lo! It’s out of ink and, providing you can find it, you’re the lucky one who gets to take out the old cartridge and replace it with the new. Or someone else needs the printer and they don’t know how to replace the ink cartridge, and your new husband looks at you when you come home and says, “You got stuck with changing the ink cartridge again, didn’t you?” But around 11 o’clock of a one o’clock night, the guys order out. You all sit around eating and telling funny stories, then haul your butt back to work. Everyone cheers you when it’s all finally done, and they order car service to take you home, and tell you to come in at noon in the morning. The job isn’t so bad.

Secretary, Prudential Bache Capital Funding, New York City, New York, 1988 – 1989: Steve decided to make a move south (the southern point of Manhattan), to Prudential Bache, and he invited me to come with him. We both knew there was a move to dissolve Investment Leasing afoot, and he thought he could start moving up the business ladder again at Pru. It broke my heart to leave my friends at Chase, but I went with Steve, thinking I could deal with his warning of “it’s more corporate.”

I couldn’t, really. I was put to work on their computer system a week before I was trained in it, which led to watching streams of numbers eat themselves, while I had no idea where to look for them. Our bosses weren’t our bosses—our bosses were two women who oversaw the secretaries by micromanaging. We were not allowed overtime. We were also not allowed to make up a late (15-30 minutes) arrival by working later. And our clothes were scrutinized. I had two bosses, Steve and a woman I admired but didn’t like. Having two stress monkeys on the same team is always bad, and when one of them is the boss and the other is a Red who believes she is as good as a Boss, well. She also would change her travel plans two or three times before her departure, and again before her return. And because I sat right in front of the Big Boss for the section, he would shanghai me if he didn’t see his own secretary at her desk. It turned out I also worked for the intern.

By January I was losing whatever was in my stomach every morning before I left, and then my lunch. Dinner was the only meal I could keep down for three weeks, as long as it was potatoes, or macaroni. I was a wreck. Finally I asked Steve if I could take him to lunch. Of course, he knew what I was going to say before I said it. He said he understood. I hung on until April, before I quit. I stopped losing my lunch the moment I knew I was going to quit.

Temporary/Permanent Secretary, New York City, New York, 1989 – 1992: This is kind of a blurry time. I returned to Investment Leasing, first as a temporary secretary, then as a permanent secretary, working for Vic, his boss Frank, and whoever needed me. The department was losing people left and right as work drifted around that they were about to be combined with Investment Leasing from New Jersey. We were given the choice of staying or changing, and we all changed, since we knew the head of Investment Leasing from New Jersey. Our entire computer section up and left together. Rosanna left when her boss did, and started work with a big firm uptown. Rosemary quit before I returned, and Rose was planning her retirement. I found a job in the Domestic Banking section, working for a computer geek of fifty who was said to like almost no one (he liked me, for some strange reason, and I liked him, but I’m married to a geek), and another banker, plus a very cheerful ex-jock 2VP who ran lots and lots of numbers.

I quit before I got fired for multiple absences (my migraine headaches went wild, this time). I returned to temporary work, spending a great deal of time at an insurance law firm where the prevailing atmosphere in the secretarial pool was that of a middle school, where the reigning clique of pretty girls made fun of anyone who was overweight or poorly dressed.

In the meantime, I had begun to put a few things together. I was making enough money from my English and German royalties that I could just squeak by. I had just sold a quartet to Scholastic and had two more books to go at Simon & Schuster. I had learned how the old men at Castle Clinton got sparrows to eat from their hands (I was working on the Daine books at the time). Why was I still donning uncomfortable clothes and shoes and jamming myself onto the subway when I could tell myself I didn’t need cookies or more books and write? Tim was working two jobs, so he could pay his bills. When I talked it over with him, he didn’t even hesitate. He said, “Do it.”

So I did. I kept the secretary clothes at the back of the closet, just in case. We had some very lean years, but we hung on, and the years got less lean. I published more books, and publishers overseas bought and published more of my books. I found a publisher for Kel, and began to do more appearances.

And the only correspondence I type is my own.

Personal Sketches, Tammy Speaks